PRESENTATION

Women in the Attic is a podcast series that reconstructs the evolution of feminism in the West between World War I and World War II, looking at leading female personalities in the cultural and artistic milieu of the first half of the last century through their correspondence with their lovers, themselves influential figures of the time.

The title is inspired by Bertha Mason, a character from Jane Eyre (1847) and the protagonist of Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), consort of the enigmatic Rochester, locked up in an attic because she was considered insane, The Madwoman in the Attic, precisely.

The aim of the project is to give a voice for the first time to great women, artists, intellectuals and scholars, particularly emancipated and enterprising, who were often sacrificed and repudiated not only because of their feminist and anti-patriarchal sensibilities, but also because they were overshadowed by important personalities of the artistic and cultural milieu of the time, to whom they were sentimentally attached.

In order to give voice to these women and delineate their personalities, the podcast will use as a unifying feature their love and private correspondence, which will be echoed in their works, writings and diaries. The intention is to delve into the soul of each one of them, allowing them to reveal themselves, through the words of love, anger and jealousy, desire and disappointment with which they filled their most intimate dialogues with those loves that so deeply marked their lives. Reflections, feelings and impulses in those passionate confidences of theirs that express an audacity of thought and a thoroughly modern consideration of the role of women in art and in the world. The intent of the format is to portray these women in all their contradictions, weaknesses, strengths, victories and defeats, avoiding reducing them to banal clichés and simple feminist icons, freeing them from reductive preconceptions to portray them as the complex and multifaceted persons they were.

Deeply immersed in their time, their writings reveal not only their life experience, but also the social and cultural vision of women in those years. The literary production is complemented by a focus on the socio-historical dynamics of the period.

Advertisements, newsreels, articles, reports: numerous archive materials, in writing when not already in sound, will immerse the listener directly into the era of the protagonists. The project not only aims to understand their way of being, certainly a break with the homologated thinking of the time, and a society anchored to patriarchal and retrograde systems, but also intends to explore their work, the indelible marks they left through their art: the characters of their pen, the objects of their discoveries, their high contributions to human knowledge and social thought.

In particular, the podcast will focus on their feminism, often ante-litteram, at once polite and shameless, which was made manifest not necessarily through slogans and angry demonstrations, but in their refined yet scandalous works, an expression of their revolutionary lives, breaking with the socio-cultural context of which they were often the slaves.

It will be explored how these women experienced, narrated, often becoming victims and losing themselves, the amour fou, in the sense of burning passion, with strong sexual connotations. These are women who have discovered and described their sexuality without qualms, breaking the chains that bound women at the time to a mere object of desire, often relegating them to the passive role of angel of the hearth, cornerstone of conjugal well-being and procreation. These women became the subject of desire, thus overturning strongly ingrained canons and subverting pre-established roles, savouring sexual pleasure with freedom, often toward their own sex and outside marital or monogamous relationships.

These are women who paid the price for such ‘licentiousness’, being judged, blamed by the rigid and intransigent society of the time, sometimes branded as insane, so that they were locked up in special institutions, removed and segregated, like Bertha Mason almost a century earlier.

The podcast will focus on the theme of madness and mental illness with which these great women have often been associated. Accused of madness, of moral insanity, of schizophrenia, they were driven away and isolated by the very men who saw their freedom of thought and creativity as a threat to their egos and their art. Victims, therefore, of those same passions that inspired them, crushed by social dynamics and a male chauvinism too petty to give space to their creativity and non-conformist spirit.

THE PROTAGONISTS

The podcast will be structured in nine episodes, which will explore the lives and passions of nine women who were particularly significant for their contributions to the cultural and artistic landscape of the time, as well as for their unprejudiced and independent lives. This will be done primarily through their epistolary relationships with prominent personalities of the period.

Amalia Guglielminetti

My dear Guido, I did very wrong to embitter you with my bitterness, it is I who must accuse myself, not You. I did not wait for you yesterday. I spent the day in a vague, non-anxious suspension, thinking that a cause

independent of your will certainly held you back.

But you cannot leave like this. You will come on Wednesday: you will not ask my forgiveness, we will not

explain ourselves, we will not say anything. We will only leave our souls a little close and our hands

a little joined before we part for a long time. It will be a small dream respite for you and me. We will forget that there are things and men and women. We will feel that we are alone in the world, or that we are outside the world. If you wish to watch we will watch each other in silence, if you wish to sleep you will rest your head on my shoulder.

And then we will say goodbye. Come.

A.

(1907)

Zelda Fitzgerald

Something in me vibrates with a dusky, dreamy smell – a smell of dying moons and shadows -I spent today at the cemetery. It’s not a real cemetery, you know – trying to open the lock of a rusty crypt built into the side of a hill. It’s all overgrown and covered with watery blue flowers that could have grown from dead eyes – sticky to the touch and smelling sickly – The boys wanted to get inside to test my courage – tonight…why should graves make people feel they live in vain? I’ve heard it so often and Grey is so convincing, but for some reason I find nothing desperate about having lived – all the ruined columns and clenched hands and angels mean love stories – and a hundred years from now I think I’ll enjoy young people wondering if my eyes were brown or blue – obviously, they are neither one nor the other – I hope my grave looks like it did many many years ago – isn’t it funny how, out of a whole row of Confederate soldiers, two or three make you think of departed lovers or loved ones – when they look exactly the same as the others, even for the yellowish moss? Ancient death is so beautiful – so incredibly beautiful – We will die together – I know –

(1919)

Milena Jesenká

Milena,

what a rich, heavy name, difficult to lift because of its

fullness, and from the beginning I did not like it much,

it sounded to me like a Greek or a Roman lost in

Bohemia, raped in Czech, deceived in the accent, and

yet, in shape and colour, it is marvellously a woman

who carries herself on her arms out of the world, out of

the fire, I don’t know, and she lays herself docile and

trusting on my arms, only the strong accent on the i is

bad, the name does not chase me away? Or is it just the leap of happiness that I myself make with this weight?

(Kafka, 1920)

Vita Sackville-West

What an upset to arrive in London and find that you are not there. An empty London, despite its eight million inhabitants, or however many. (…) Are you OK? Is it sunny? Oh, and Orlando. I forgot. You literally terrified me with your “Do I exist or did you invent me?” remarks. I always predicted this would happen once you took Orlando down. Well, I’ll tell you one thing: if you like me – no indeed if you love me – even a smidgen less now that Orlando is dead, know that you will never lay eyes on me again, except by chance at one of Sybil’s parties now. I do not want to be a sham. I don’t want to be loved only in an astral body, or in Virginia’s world.

So hurry up and write to me and tell me I’m still real. I feel terribly real, right now – like clams and mussels, all alive – oh.

(1928)

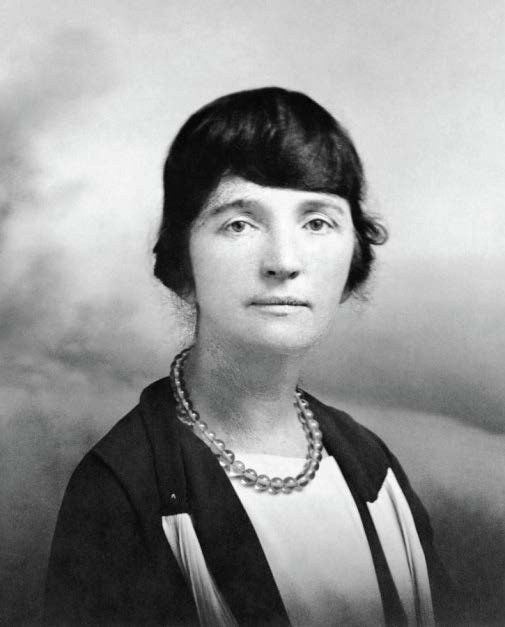

Margaret Sanger

At times I have been disheartened and demoralised by the

deliberate misinterpretation of opponents of the birth

control movement, and the explicit tactics used to fight it.

But in these moments I am inevitably reminded of the

vision of America’s enslaved and pleading mothers. I hear

the grave cries of their cries for liberation – a vision

constantly renewed in my mind by the reading of these letters. As painful as they are, they release new resources of energy and determination. They give me the courage to continue the battle.

(1945)

Sabina Spielrein

Dear Doctor (…).

She often saw that I was serious about my musical

‘inspirations’. The more I work on musical compositions, the more I feel drawn to music, despite all resistance and criticism. (…) Reason tells me that I have to give up the musical ‘goal’ because I will do more in the scientific profession, but if I follow my feelings, I cannot do without music: it seems that along with music I feel a part of my soul being torn away and the wound never heals. Is it neurosis? Why yes? Is it not? Why not? Why not, after all, assume with Freud that I belong to the ‘saviour and victim type’ and therefore represent my desires with symbols that express the total dissociation of the personality, like for example all great heroes, who die for their ideals, (…) like music, which more than all other arts requires total dedication?

What do you think about all this?

Many questions still arise in me, but that’s enough for now (…)

With best regards,

S. Spielrein

(1918)

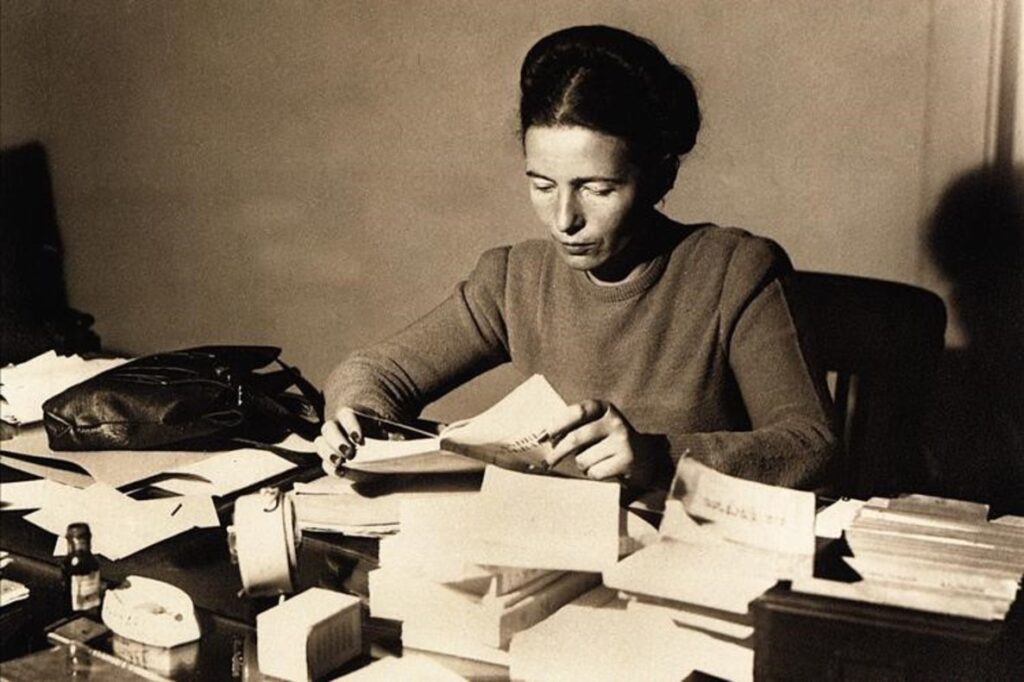

Simone de Beauvoir

Tout cher petit être,

I received your letter this morning…I keep it in a secret pocket of my bag and I think I will read it every day (…) Yesterday… Védrine… slept at my place (…), we had a passionate night, the passionate force of this girl is crazy; sensually I was more taken than usual… there was an awareness of having a sexual attraction without tenderness, something that has practically never happened to me. (…) My love… there are only you in the world who matter to me: neither people nor places, I don’t care about anything. – I would start a new life with you, making a clean slate of everything, of Paris, of money, of everything, with joy: I only need you and a little freedom – I love you: – …And I am so happy, because I have nothing to tell you about my love that you don’t know as well, mon cher amour.

Votre charmant Castor

(1939)

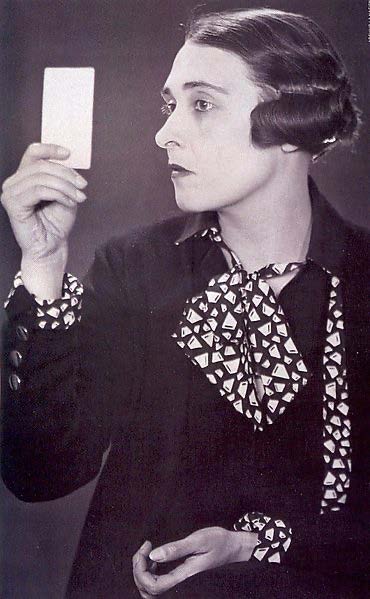

Victoria Ocampo

Gurudev (a thousand times dear…):

I have to admit that I miss you guys too much. It is becoming absolutely uncomfortable, absolutely embarrassing, because I cannot think of anything else. (…) Your letter from Rio (5 Jan.) arrived this morning. When I recognised your handwriting on the envelope, my heart gave a leap, a terrible leap (luckily I was in the garden, otherwise my heart would have hit the ceiling badly! As it was, it only bumped against the sky). Looking at that envelope was a joy you cannot even imagine. (…)

I think you exaggerate when you talk about the ‘profound dignity of the male’. It is obvious that males are by nature useless. Of course it is cruel to force them into the form of ‘useful members of society’. It is not their true form. In Fabre’s book on insects, I read that, in some species, the wife (?) eats the husband (?) when she is tired of him and feels that he is no longer useful. I think this is the right way to settle things! (…)

(1925)

Jean Rhys

There is no mirror here and I don’t know what I look like

now. I remember looking at myself brushing my hair, and I

remember my eyes staring at me from the mirror. The girl I

was seeing was me, and yet it was not really me. A long

time ago, when I was still a child, and so lonely, I tried to

kiss her. But the mirror separated us – hard, cold and

fogged by my breath. What am I doing in this place and

who am I? The door to the room with the tapestries is always locked. I know it leads into a corridor. (…) When night comes, and after many drinks, she is asleep, it is easy to get the keys. Now I know where she keeps them.

So I open the door and enter their world. As I have always known, it is a world of papier-mâché. I’ve seen it before, I don’t know where, this world of papier-mâché where everything is brown or dark red or yellow without splendour. As I walk down the corridors, I wish I could see what is behind the papier-mâché. They tell me we are in England but I don’t believe it. We have lost our way to England. When? Where? I don’t remember, but we lost it. (…) This papier-mache house where I walk at night is not England.

(Wide Sargasso Sea, 1966)

LIST OF EPISODES

The series can potentially be extended to other episodes. In this first cycle we propose the following couples:

- Amalia Guglielminetti (1881-1941) and Guido Gozzano (1833-1916)

Born into a bourgeois family in Turin, despite the strong religious upbringing she received, Amalia was always considered to be at the antipodes of the female canons of her time, having embodied with her life and works an ideal of free love, and having approached a Sapphic sphere with her poetry. An established poetess, she met with success and critical acclaim with her book Le Vergini Folli (1907), which was written about by the poet Guido Gozzano, with whom Amalia established a passionate relationship later witnessed by a rich epistolary. Guglielminetti’s work takes the form of a journey into the dimension of female virginity described in a crepuscular and D’Annunzian style. The central theme of his work is therefore the desire of women to overturn the role assigned to them in contemporary society, through the representation of free and non-conformist women, marked by a marked nonchalance in living their sexuality both within married love and in a Sapphic relationship. In 1935 she moved to Rome to unsuccessfully attempt a career in journalism, then returned to Turin where he spent the rest of his life in solitude. On her tombstone she had a summary of her life inscribed: ‘She is still the one who goes alone.’ - Zelda Sayre (1890-1848) and Francis Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1940)

A writer, publicist, occasional painter and dancer for pleasure, Zelda was considered a proto-feminist for her unconventional behaviour. A flapper icon of the prohibition era, of the consumerism typical of the Roaring Twenties, committed to living the ‘grand resplendent flow of life’, Zelda is mostly known for her passionate and tormented relationship with her husband, Francis Scott Fitzgerald, whose muse, critic and rival she was. An acute lifestyle journalist, a controversial and emancipated feminist, she wrote not only articles on the modern woman such as In Praise of the Flapper or What Happened to the Flapper? but inspired with her letters, stories and her own diary the work of her husband, who even signed articles written by Zelda in his name. The two formed the most seductive and fashionable couple of the time, amidst feasts, poetry and excess, always together in a truly mobile party. But what lay behind the social chronicles was something else entirely. His debts, jealousy and alcoholism as well as her instability soon unravelled that paradise of theirs, making Zelda the victim of a marriage bordering on the despotic, a prisoner in a cage built by her own beloved who, jealous and envious, could not stand her freedom and creativity, to the point of showing angry displeasure at the publication of Zelda’s autobiographical novel Save me the Waltz (1932), written while she was a patient in a psychiatric clinic. A segregated woman in a high tower, Zelda spent the last years of her life going in and out of psychiatric clinics due to her diagnosed schizophrenia, an imbalance that seemed closely linked to her husband’s intrusive presence and Zelda’s now bent will to break free, excel, and create. She died in a fire inside the Highland Hospital where she was admitted. Only her slippers were found. - Milena Jesenská (1896-1944) and Franz Kafka (1883-1924)

Czech-born journalist, writer, translator and committed intellectual. Curious from an early age, Milena, against her father’s wishes, married Ernst Pollak, a Jewish intellectual and literary critic, whom she met in Prague’s literary circles and with whom she moved to Vienna. In 1919 she was thunderstruck by reading a short story by Franz Kafka, to whom she wrote asking his permission to translate it into German. It was thus that she became ‘Kafka’s friend’: the two began a close correspondence that turned into love, although they only met twice in Vienna and Gmünd. Milena, in addition to acting as translator for the Czech writer, began to write articles herself for the magazines of the time. Returning to Prague after her divorce, she continued with her work as a committed intellectual, writing for various newspapers, covering current social issues such as abortion or censorship, and then devoted herself to reports and editorials on the rise of the Nazi party, anti-Semitism and the annexation of Austria. Following the occupation of Czechoslovakia by the German army, Milena joined the underground resistance movement, helping to expatriate many Jews and refugees and, while continuing her work as an intellectual, turned her flat into a sort of headquarters for Czech, British and even German resistance fighters. In 1939, she was arrested by the Gestapo and later taken to Ravensbrück concentration camp in Germany, where she died. - Vita Sackville-West (1892-1962) and Virginia Woolf (1882-1941)

An English poet, writer and botanist, she was famous for her work as a novelist, but also for her ‘unhinged’ life, her numerous lovers and her relationship with Virginia Woolf and Violet Trefusis, as well as her ‘open’ marriage to Harold Nicolson, who was also attracted to people of the same sex. A great traveller, she often travelled to France and Persia, where her husband worked. Virginia Woolf, who met Vita in 1922, introduced her to the Bloomsbury group, an artistic-literary movement born in 1905 in London, whose members, mostly liberal and non-conformist in political as well as in moral, sexual and religious spheres, met in private houses in the district from which they took their name, until the Second World War. The relationship between the two lasted for a good ten years and coincided with the artistic apotheosis of both, linked to the positive influence of one on the other. To her Virginia dedicated Orlando (1928), a literary transfiguration of their love. Buried in the book, this love came to an end a few months after publication. Despite her vast literary oeuvre that includes travel narratives, novels, poems, family chronicles as well as auto-biographical tales, almost all published by Hogarth Press, the Woolf’s publishing house, Vita’s perhaps most innovative and outstanding flair is linked to gardening, of which she was a great enthusiast and expert: for 15 years, from 1946 to 1961, she kept a column in the “Observer”, published in Italy under the title Il Giardino alla Sackville-West. Her most important legacy is in fact the garden of Sissinghurst Castle, the most visited in England, now owned by the National Trust. - Margaret Sanger (1879-1966) and Herbert George Wells (1866-1946)

American activist, writer, nurse and sex educator, pioneer of contraception and reproductive rights. She was the first to use and popularize the term ‘birth control’ and opened a clinic in the US that would become what is now Planned Parenthood. A nurse in the slums of the Lower East Side, she soon threw herself into radical politics and joined the women’s committee of the New York Socialist Federation, participating in struggles and strikes. Author of articles on women’s sexuality and sex education in general, Sanger strenuously opposed abortion as a social danger to public health, seeking other avenues that could free women from the danger of unwanted pregnancies and promote the empowerment of the working class. Thus, it was that in 1914 she launched The Woman Rebel, a monthly newsletter promoting contraception and challenging existing federal anti-obstacle laws, followed closely by Family Limitation, a pamphlet containing detailed information on various contraceptive methods, publications that forced her into exile in England. Her repeated arrests and her trial secured her the interest of the public and the support of many. In 1920, during a visit to Essex, she met the writer Herbert George Wells for the first time, with whom she had an intermittent but fervent relationship, kept alive by a commonality of purpose and a prolific exchange, as can be seen from their dense correspondence that lasted until their death. It was with the founding of the American Birth Control League that he also succeeded in gaining the support of the middle class by extending his collaboration to Japanese feminists and prominent leaders of the African-American community. Planned Parenthood, however, remains Sanger’s true legacy, soon rising to the role of the largest international non-governmental organisation for public health, family planning and birth control. - Sabina Spielrein (1885-1942) and Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961)

Born into a wealthy family in the Soviet Union, from a very young age she suffered from a form of depression that forced her to be interned in Zurich under the care of Carl Gustav Jung, who diagnosed her with a form of hysterical psychosis. Once cured, Spielrein began a seven-year relationship with Jung, and also enrolled at the medical faculty in Zurich to specialise in psychoanalysis, graduating in 1911 with a thesis on a case of schizophrenia. In the same year Spielrein and Jung broke off their relationship, which had been exacerbated by her desire to have a child with Jung, who was married at the time. Spielrein therefore moved to Vienna where she married a Russian doctor and had a daughter. Only ten years later she returned to Russia and founded a psychiatric hospital for children in her home country, based on very modern principles for the time, which was in fact closed shortly afterwards by the Soviet authorities. Although Stalin outlawed psychoanalysis in 1924, Spielrein continued to practice it illegally in private. She was murdered by the Nazis who had occupied her hometown from which she had refused to flee. Her contribution to psychoanalysis was remarkable: she was the first to introduce the idea of the death instinct later adopted by Freud and to spread psychoanalysis in Russia. - Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986) and Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980)

Writer, philosopher, key figure of second-wave feminism. A philosophy graduate from the Sorbonne, she met Jean Paul Sarte, the father of existentialism, in 1929 during one of the many seminars the two attended at the Sorbonne University in Paris: both model students, both animated by the desire to deconstruct the dogmas of the respectable bourgeoisie that had generated them. From then on, their paths were inextricably linked; for 51 years, the two intellectuals maintained an atypical but indissoluble relationship: they never lived under the same roof, rejecting marriage and all the conjugal duties associated with it, considered legacies of the past and impediments to the full realisation of their potential. They thus formed an original, non-exclusive couple, based on ideas of necessity, freedom and transparency. One of their most representative ways of understanding life as a couple was represented by the agreement that Sartre and Simone used to regulate their relationship: driven by the desire to shun the institution of marriage at all costs, the two stipulated a special contract, renewable every two years, which had only one clause: infidelity perceived as a reciprocal duty, a sort of insurance against the lies, subterfuges and hypocrisies of bourgeois marriage. De Beauvoir taught until 1943, devoting herself, after the success of her first novel L’invitée, solely to writing. In 1945 she founded, together with Sartre and others, the magazine Modern Times, which aimed to give space to committed literature. In 1949, she published Le Deuxième Sexe, which became a pivotal essay of feminism, although De Beauvoir did not call herself a feminist until 1970: ‘I became one especially after the book existed for other women’. Indexed by the Vatican, flogged by both left and right, the book was based on the assumption that ‘woman is not born, she is made’. In order to accurately describe the nature of women, the philosopher rejected notions such as ‘eternal femininity’, arguing that it was necessary to overcome the debate on superiority, inferiority or equality between men and women by starting from scratch, with other terms. According to De Beauvoir, in order to escape her own condition of imposed inferiority, every woman must pursue her own emancipation through the achievement of economic and cultural independence. - Victoria Ocampo (1890-1979) and Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941)

Argentine writer and intellectual, described by Borges in his The Quintessential Argentine Woman, best known as an editor and literary critic. She was born in Argentina, into an aristocratic family that made her study privately. Passionate about literature and languages, she initially approached writing as her own intimate outlet and wrote her first articles in French. During a tennis match she met her first husband, Luis Bernando de Estrada, a nobleman from a Catholic and conservative family, from whom she divorced due to his possessive and jealous attitudes. In 1924 Ocampo met the poet Tagore, having to write an article about him for the newspaper La Nación, and thus spent two months with the writer in a villa in San Isidro, near Buenos Aires. It was here that a relationship of mutual admiration and empathy began between the two, which was recorded in a lifelong correspondence. Ocampo’s most notable cultural contribution was her work as the founder and editor of the magazine Sur in 1931, in which texts by important writers such as Jorge Luis Borges, Adolfo Casares and Julio Cortázar, as well as other foreign authors, in particular French, English and American, were published. In 1953 Ocampo was arrested for her overt opposition to Perón, a fact that also forced her to resign from her position at the magazine Sur. Victoria Ocampo was the first woman to enter the Argentine Academy of Letters. She was also the founder of one of Argentina’s oldest feminist movements, the Union de Mujeres (Women’s Union), a member of the International Pen Club and received an honorary degree from Harvard University. - Jean Rhys (1890-1979) and Ford Madox Ford (1873-1939)

Caribbean, but isolated as white and Creole in a black community; English, but mocked for her colonial origins; a talented writer, but only recognised as such late in life: Jean Rhys has always been an outsider and her intense life, full of difficulties and twists and turns, has been a constant struggle to rise up and reassert herself. Born in the Caribbean to Creole parents, she was sent to London when she was only 17. A forgotten voice of the 20th century, she told stories of uprooted and criticised women within society. In the 1920s, having moved closer to modernist reading, but increasingly devoted to alcohol, an attachment that would never abandon her, Jean Rhys wrote her first works: stories of women torn from their roots, exploited and rejected by the very society that allowed all this. Thanks to her frequent visits to Paris, she met Ford Madox Ford, with whom she started an abusive relationship that included his mistress, later narrated in her autobiographical work the Quartet (1928). It was through her encounter with Ford that Rhys was able to enter the literary circles of the time, thus furthering her career as a writer. The narrative of her life, however, between abusive relationships and broken marriages, alcoholism, prostitution, an abortion, even an arrest as well as a stay in a psychiatric hospital, prevented her from living completely for her art and forced her to remain inextricably linked to a string of men, depending emotionally and financially on them due to her alcoholism. Perennially in search of a sense of belonging, a stranger wherever she went, Jean Rhys managed to give voice to the marginalised, often women reduced to madness by men who, after loving and using them, had then abandoned them, humiliated them. This is the case of The Great Sargasso Sea (1966), the writer’s most successful work, the story of Rochester’s first wife driven mad by love for him and then segregated in the attic, a woman who was also the victim of an adverse fate.

EPISODES DESCRIPTION

The duration of each episode will be between 20 and 30 minutes.

Each episode will be devoted to a couple, but in some cases, as in the case of Zelda Syre Fitzgerald, it is possible that the story will be spread over several parts.

Excerpts from the protagonists’ letters and works will form the structural skeleton, framed by historically authentic period materials such as newspaper articles, reviews, period advertisements, radio and archive materials.

The narration of their lives, like that of their love affairs, will be rendered not only through the reading of their writings, personal and otherwise, but also through the re-enactment of authentic scenes representing their most salient moments, in the style of old radio dramas.

Whenever possible, the episodes will follow the flashback structure, where the woman, now out of the public eye and at the turn of her life, concerns herself with her past.

Music and sound will play a fundamental role, not only in historically setting the narrative, but as a real narrative device that, with specially created sounds, accompanies the mise-en-scène and the reading of many documents.

Extensive use will be made of background sound (e.g. distorted sounds of an out-of-tune radio, typewriter keys, the reception of a telegram) to evoke environments and situations typical of the atmosphere of the time. The music, strictly of the period, serves not only as a soundtrack to the narration and reading of the works, but as a true narrative link.

The episodes will thus indicatively consist of:EPISODES DESCRIPTION

The duration of each episode will be between 20 and 30 minutes.

Each episode will be devoted to a couple, but in some cases, as in the case of Zelda Syre Fitzgerald, it is possible that the story will be spread over several parts.

Excerpts from the protagonists’ letters and works will form the structural skeleton, framed by historically authentic period materials such as newspaper articles, reviews, period advertisements, radio and archive materials.

The narration of their lives, like that of their love affairs, will be rendered not only through the reading of their writings, personal and otherwise, but also through the re-enactment of authentic scenes representing their most salient moments, in the style of old radio dramas.

Whenever possible, the episodes will follow the flashback structure, where the woman, now out of the public eye and at the turn of her life, concerns herself with her past.

Music and sound will play a fundamental role, not only in historically setting the narrative, but as a real narrative device that, with specially created sounds, accompanies the mise-en-scène and the reading of many documents.

Extensive use will be made of background sound (e.g. distorted sounds of an out-of-tune radio, typewriter keys, the reception of a telegram) to evoke environments and situations typical of the atmosphere of the time. The music, strictly of the period, serves not only as a soundtrack to the narration and reading of the works, but as a true narrative link.

The episodes will thus indicatively consist of:

o Reading of selected epistolary letters from these women

o Reading of extracts from their works and private writings

o Re-enactment of particularly significant moments in their lives

As narrative links, they will be used instead:

o Reading articles, materials and historical documents of the time

o Advertising and vintage radio material

o Period music

The intention is to draw the listener into the intimate and personal sphere of the protagonists, thus giving voice, for the first time, only to them. They will be placed in sharp relief and also in contrast to the cultural landscape of the time, so as to bring out how much their lives and behaviour were alternately admired and denigrated.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

To speak of feminism in the West in terms of a unitary movement is certainly implausible, although we can recognise a common thrust from a certain moment, identifiable with suffragism in the second half of the 19th century. In 1865, in fact, Great Britain, the epicentre of European feminism, saw the birth of the first committee for the extension of the right to vote to women, until then confined outside the public scene, often in the shadows, relegated to the domestic environment, following in the footsteps of the bourgeois model imposed in the 19th century that paradoxically limited them more than their non-bourgeois ancestors. Much excitement, therefore, was caused by the suffragettes’ march on Manchester and London committed to claiming what, a short time later, thanks to their efforts, many women would finally be able to achieve. The struggle was long and difficult and, before concrete achievements, it was necessary to wait until the 20th century, when the right to vote was finally extended to the female component of the population until the long-awaited universal suffrage was achieved.

The feminism of the first decades of the last century was a ‘feminism of equality’: if the feminism of the 1960s was dedicated to the liberation of women, the preceding feminism demanded due equality for women, thus attempting to put an end to discrimination, exclusion and even more subordination. It demanded equality: in rights, in professions, in public office, freedom in the management of work, family and property, and rightly demanded the vote, which was granted by Finland first, in 1906. This was followed closely by Germany in 1918, England in 1919 and the United States in 1920. Italy and France had to wait until after the war.

In Common Law countries, although it did not immediately undermine the ‘traditional’ division of roles, it was made easier by the presence of factors such as an early liberal tradition, rapid industrialisation, a Protestant ethic sensitivity to the rights of the individual, as well as those already present feminist movements that significantly influenced public opinion. The slower emergence of the movement in countries of Latin tradition was mostly due to the conservative stance of the state and the Catholic Church on gender relations as well as the imprint of the Napoleonic Civil Code.

At the outbreak of the First World War, despite the feminist revolution taking place at the level of customs, culture and mindset, no concrete results were achieved in the majority of countries, perhaps due to internal divisions that soon became apparent. Feminism, however, did not manifest itself as a unified thrust, rather it became anchored in various socio-political ideas, not only transversal to different countries, but also within them. In Italy, in 1908, the year in which the first National Women’s Congress was held in Rome, some divisions related to a bourgeois, socialist, Catholic type of feminism became evident, which had their effect in the approach to the war.

Among the more open episodes of non-interventionist pressure was the famous demonstration in the streets of New York in favour of a cessation of hostilities, a true testimony to women’s desire to have a say in matters such as peace and war, normally the prerogative of men, and the Conference of Socialist Women (which had almost become an autonomous movement), held in Berne in 1915. The pacifist and internationalist movements of the period were numerous.

However, there was no lack of interventionist impulses: democratic interventionism involved a not indifferent slice of the European emancipationist movement. Faced with the poor results of the socialist parties and liberal states, women saw in their participation in the war an opportunity for social and political recognition, not only as citizens, but as true patriots of the modern nation-states, as if they had wanted to ‘deserve’ the right to vote.

It was a series of factors related to the war that actually changed the situation for women.

The First World War, as is well known, was characterised as frontline warfare. This led women to take on roles traditionally entrusted to men. They became breadwinners, factory workers, clerks: the hard core of the workforce, responsible for subsistence, as well as emotional, material. Active even in the women’s auxiliary corps (40,000 are the British Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps), they served on the home front as well as on the front line, building one of the most iconic figures in the collective wartime imagination, that of the ‘Red Cross Woman’.

At the end of the war, despite the hostile reaction towards the more ‘masculine’ attitudes of women, the number of countries that ‘granted’ (as a sort of ‘kind concession’) the right to vote grew. France and Italy still had to wait, but already in the first years after the conflict the first partial openings took place.

In France, a ‘universal’ suffrage limited to municipal elections was granted in 1925, the same year in which Mussolini, before the total abolition of the right to vote, granted partial administrative suffrage, following the Sacchi Law of 1919, by which women were admitted to professions and public employment.

Between the two conflicts, it was even more difficult to create an autonomous and unified women’s movement, instead a model of emancipation emerged that would remain fundamental until the 1960s: the modern woman, wife, mother and worker. Hence a different way of relating to sex, motherhood, one’s own body, professional, artistic and sporting ambition, etc.

This, then, is the model of woman to which Women in the Attic wants to refer, the one that emerged as early as the 1920s.

DECLARATION BY THE AUTHORS

We discovered by chance recent publications of love letters from some of the protagonists of Women in the Attic that immediately caught our interest.

We, thus, chose to delve into that universe of love letters between artists and great thinkers, which can still convey so much to us.

Real women, authentic heroines who have long been relegated ‘to the attic’ and whom we have chosen to bring back to life not only to give their work its deserved value, but also to free them from the usual epithets of wife or lover ‘of’, allowing them to shine in their own light. Indeed, we believe that their feminism still has much to teach us.

Amalia, Zelda, Vita, Milena, Sabina, Jean, Victoria, Margaret and Simone have been able, in different places and situations, to cope with bitter difficulties linked to a patriarchal world and an often rather sexist artistic and cultural environment. Even more than with their characters and their storytelling, it is with their example that they expressed themselves at their best: with their rebellious, always non-conformist, courageous path. They lived, in a word, free, with that freedom that made them true pioneers of their era, still forerunners of a radical upheaval of roles. We have chosen to bring out the profile of these women through the personal letters they addressed to their lovers, thus avoiding the coldness of an external approach in favour of a more intimate one. It is thus through the intimacy of a confidence that each of the nine will reveal themselves, and in our view this is the power of the operation of Women in the Attic. In fact, the listener will not only be immersed in the work of the protagonist and her era, but will become a secret and privileged spectator through her most authentic thoughts, as if she were confiding directly to him.

In an era that is still strongly patriarchal, in which the feminist struggle appears to be limited to pure instances rather than to genuine equality, which is not always achieved, nor even less demanded by those who should demand it by right, it is of great importance to bring to light these figures who caused such scandal one hundred years ago and who continue to guide us and serve as an example, allowing us to shake up entrenched social attitudes, and to bear witness to the possibility of transgression, freedom of thought, action and expression.

Although we focus on the 1920s for reasons already expressed here, it is evident that the podcast format can also be extended to other historical eras. In fact, we are planning a forthcoming extension of the cycle with two additional seasons, one of which will cover the second half of the 19th century and the other the 1950s and 1960s.

In truth, there are many women who have made history, many yet to be discovered. All that remains is to dust off the attic!

SOURCES AND MATERIALS

For the couples’ correspondence.

Amalia Guglielminetti and Guido Gozzano: G. Bianchi, S. Raffo (eds.) Lady Medusa: life, poetry and loves of Amalia Guglielminetti, Bietti, Milan 2012

Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf: E. Munafò (ed.), Write Always at Midnight: Letters of Love and Desire, Donzelli Editore, Rome 2019

Victoria Ocampo and Rabindranath Tagore: M. Del Serra (ed.), Non posso tradurre il mio cuore: Lettere 1924 – 1940, Archinto, Milan 2013

Sabina Spielrein and Carl Gustav Jung: A. Carotenuto, Diary of a Secret Symmetry, Sabina Spielrein between Jung and Freud, Bompiani, Milan 1981

Margaret Sanger and H. G. Wells: New York University, The Margaret Sanger Papers Project

Jean Rhys and Ford Madox Ford: F. Whyndam, D. Melly, Jean Rhys, Letters 1931 – 1966, Penguin Books, London 1985

Simone De Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre: I. Savarino, G. Bosco (eds.), Simone de Beauvoir unveiled by letters to Sartre soldier, Vallecchi, Florence 1995

Milena Jesenká and Franz Kafka: F. Masini (ed.), Franz Kafka, Letters to Milena, Mondadori, Milan 2021

Zelda and Francis Scott Fitzgerald: Cathy W. Barks and Jackson R. Bryer (eds.), Dear Scott Dear Zelda: The Love Letters of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, La Tartaruga, Milan, 2018.

Fitzgerald Zelda, Let Me the Last Waltz and Other Writings, Elliot, Rome, 2018.

Bruccoli Matthew J., Scottie Fitzgerald Smith (eds.), The Romantic Egoists, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1974.

SOUND MATERIAL (Radio, newsreels, extracts from advertisements)

BBC radio archives (genome.ch.bbc.co.uk)

Hagley Digital Archives (digital.hagley.org)

American Archive of Public Broadcasting (americanarchive.org)

Gale: The Listener Historical Archive, 1929-1991 (galeapps.gale.com)

British Library: Radio Broadcast Recordings collection (www.bl.uk)

Istituto Luce Archives (www.archivioluce.com/cinegiornali/;

www.archivioluce.com/documentari/) RaiPlay Radio: The Specials – QUI RADIO BARI (www.raiplayradio.it)

Radio-Paris Archives – Les Radios Au Temps de la TSF (www.radiotsf.fr)

Les Fonds Radio – Ina Thèque (www.inatheque.fr)

Past Daily: Sound Archives

RTÉ Archives (rte.ie/archives/exhibitions/)

Radio Prague International – Czech Radio – Broadcast archives (archiv.radio.cz)

National Archives Museum: American Women and the Vote (https://museum.archives.gov/rightfully-hers)

British Pathé Historical Collection: https://museum.archives.gov/rightfully-hers

National Humanities Centre: America in the 1920s(http://americainclass.org/sources/becomingmodern/modernity/text2/text2.htm)

Critical Past: footages of the Roaring 20s (https://www.criticalpast.com/collections/the-roaring- 1920s-archive-HD-stock-video-footage-clips)

Curiosity Collections: Women Working 1800-1930 (https://curiosity.lib.harvard.edu/womenworking-1800-1930/catalog?search_field=all_fields)

Old Magazines Articles: http://www.oldmagazinearticles.com/magazine-articles/fashion/flappers,

http://www.oldmagazinearticles.com/draw_pdf.php?filename=flapper.pdf

Women and the American History: https://wams.nyhistory.org/confidence-and-crises/jazzage/flappers-in-media/

Library of Congress: https://guides.loc.gov/womens-suffrage-mbrs/recorded-sound

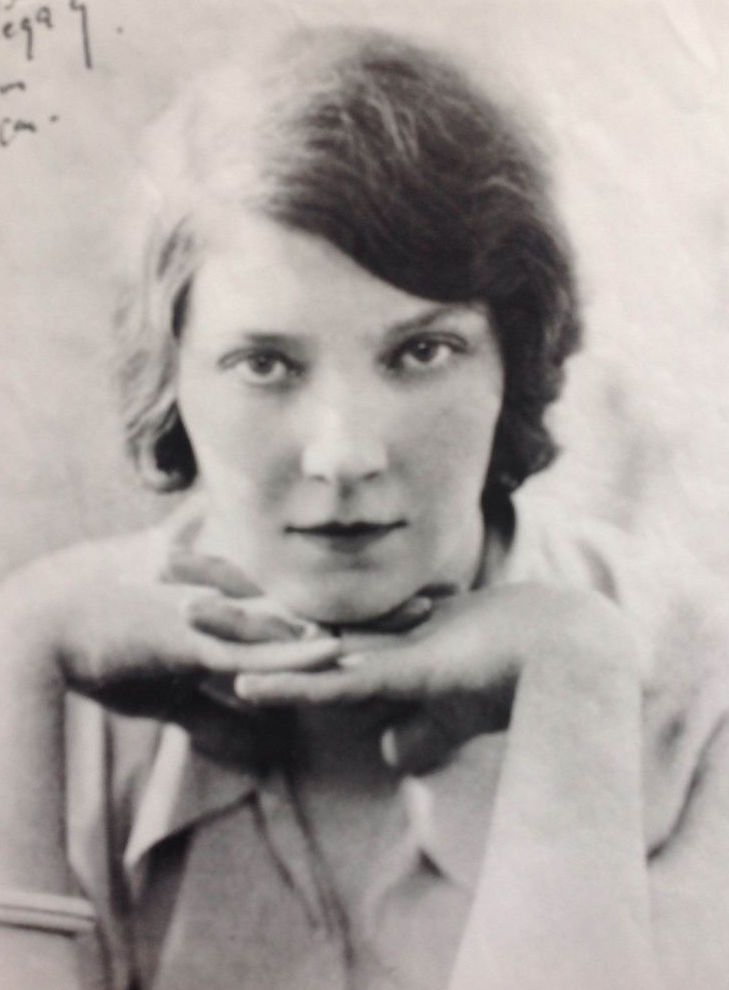

Simone De Bevoir